My Ascent of Mount Maggiore

photo gallery

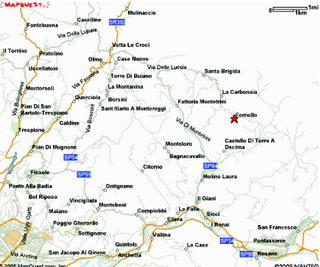

During our visit to Fornello, Brenda reminded me twice that the final day of our trip was Yom Kippur, the highest holiday in the Jewish Calendar. I wished she hadn't mentioned it so I could have let it pass unnoticed. I woke up Thursday morning feeling guilty—in part for the privilege of enjoying Italy during the time of year I would normally be staggering under my Fall quarter workload, and more specifically at the prospect of going on our scheduled gastronomic and wine tour of the Chianti region on this fast day. I hadnt attended a synagogue service in decades, but refraining from food for 24 hours and going into the woods alone on this holiday was one religious duty I had regularly observed. I decided to skip breakfast, excuse myself from the tour, and head for countryside. It took me a cranky uncaffeinated hour to negotiate buying a ticket from the Tabak shop and find the right bus stop, but by 11 a.m. I had reached Monteriggioni, where my Italian Alpine Club map indicated the beginning of an excursion leading to the top of Monte Maggiore.

I woke up Thursday morning feeling guilty—in part for the privilege of enjoying Italy during the time of year I would normally be staggering under my Fall quarter workload, and more specifically at the prospect of going on our scheduled gastronomic and wine tour of the Chianti region on this fast day. I hadnt attended a synagogue service in decades, but refraining from food for 24 hours and going into the woods alone on this holiday was one religious duty I had regularly observed. I decided to skip breakfast, excuse myself from the tour, and head for countryside. It took me a cranky uncaffeinated hour to negotiate buying a ticket from the Tabak shop and find the right bus stop, but by 11 a.m. I had reached Monteriggioni, where my Italian Alpine Club map indicated the beginning of an excursion leading to the top of Monte Maggiore.

I got off the bus and bounded up the steep pedestrian approach to the castle famously described by Dante

As, when the fog is vanishing away,

As, when the fog is vanishing away,

Little by little doth the sight refigure

Whate'er the mist that crowds the air conceals,

So, piercing through the dense and darksome air,

More and more near approaching tow'rd the verge,

My error fled, and fear came over me;

Because as on its circular parapets

Montereggione crowns itself with towers, 41

E'en thus the margin which surrounds the well

With one half of their bodies turreted

The horrible giants, whom Jove menaces

E'en now from out the heavens when he thunders. (Inferno Canto 31)

I wandered through the tiny village inside the fortress, sat for a moment in the empty chapel, and left 50 cents in the offering box. I paid a Euro to the lonely young man guarding the stairway that led to the top of the wall from which I could see the mountain towering in the mist. In the car park on the south side of the wall, I found a large sign with a maps and historical information about the trail ahead. Like the piazza between the Siena Duomo and the Ospedale, this too was part of the Via Francigena, the pilgrim itinerary from Compostela to Rome that put me on a venerable path of discomfort, wanderlust and spiritual aspiration. My route through the wilderness of "Montagnola" would take me to the summit and then on what a sign called "La Grande Traversata," down to the villages of Fungaia and Santa Columba on the other side, where I could catch another bus back to the city.

In the car park on the south side of the wall, I found a large sign with a maps and historical information about the trail ahead. Like the piazza between the Siena Duomo and the Ospedale, this too was part of the Via Francigena, the pilgrim itinerary from Compostela to Rome that put me on a venerable path of discomfort, wanderlust and spiritual aspiration. My route through the wilderness of "Montagnola" would take me to the summit and then on what a sign called "La Grande Traversata," down to the villages of Fungaia and Santa Columba on the other side, where I could catch another bus back to the city.

A dirt road led me into thick woods which occasionally opened up to fields, olive groves, and old villas and ended at an organic farm and meditation center named Ebbio, where several guests stood in the courtyard looking nervous and smoking cigarettes. Here the road gave way to a steep trail that tunnelled through forests of small trees, some thick with brush, others recently thinned and coppiced. I was serenaded by unfamiliar melodies that sounded as if they could only have been sung by birds called "larks." Exertion and solitude and the growing distance from the valley occasionaly visible through a break in the trees contributed to the pleasant buzz in my head created by the emptiness in my stomach. A small trail branched to the left which I thought might lead to the summit. I noticed a cluster of delicate pink cyclamen growing in the deep shade at my feet, fresh blooms in mid-autumn.

Exertion and solitude and the growing distance from the valley occasionaly visible through a break in the trees contributed to the pleasant buzz in my head created by the emptiness in my stomach. A small trail branched to the left which I thought might lead to the summit. I noticed a cluster of delicate pink cyclamen growing in the deep shade at my feet, fresh blooms in mid-autumn.

I followed the side trail uphill for several minutes, but rather than reaching a summit, it headed back downhill. Conscious that it was well past noon and that I hadnt seen any signs or trail markers for the last hour, I no longer could locate myself on the map with certainty. I returned to the patch of cyclamen and continued heading toward the westering sun, hoping soon to find a junction that would lead to the south and then east. The bird song had ceased and now in the distance I heard the whine of one, then two chainsaws. The trail came to a clearing at a junction of several tracks filled with deep mud, sign of the recent passage of skidders, the huge insect-like machines which drag timber out of the forest. Across a plateau miles ahead of me I could see land that had recently been cleared but no evidence of civilization or indications of where I could make my way out of this endless Montagnola. I walked faster and then half ran toward the ugly sounds of the chainsaws but seemed to get no closer and found new paths heading off in all directions. I felt stirrings of fear and confusion. I checked my watch and told myself that if I found no landmark within ten minutes I would have to admit defeat, turn around and retrace my steps. Twenty minutes later, with an unmistakeable taste of panic in my mouth, I did just that.

land that had recently been cleared but no evidence of civilization or indications of where I could make my way out of this endless Montagnola. I walked faster and then half ran toward the ugly sounds of the chainsaws but seemed to get no closer and found new paths heading off in all directions. I felt stirrings of fear and confusion. I checked my watch and told myself that if I found no landmark within ten minutes I would have to admit defeat, turn around and retrace my steps. Twenty minutes later, with an unmistakeable taste of panic in my mouth, I did just that.

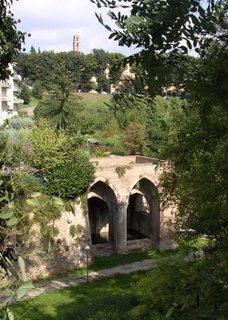

The walk back was long and boring. Having neither reached the summit nor accomplished "La Grande Traversata," once I knew my way, I took an alternative dirt road down to the valley that passed by a memorial to WW II partisans who hid in this wilderness but finally were captured and executed by the Nazis. I passed several men with guns and dogs who were out hunting, probably for larks. The road was steep, viewless and littered with trash. It emerged at Abbadia de Isola, which the historical signs told me was the site of an Abbey and military outpost for Siena that was rendered obsolete with the construction of Monteriggione back in the eleventh century. The buildings were standing, but restoration had not proceeded. Inside, on rutted dirt streets, I saw decrepit old people coming and going from apartments built into the decaying ruin.

The road was steep, viewless and littered with trash. It emerged at Abbadia de Isola, which the historical signs told me was the site of an Abbey and military outpost for Siena that was rendered obsolete with the construction of Monteriggione back in the eleventh century. The buildings were standing, but restoration had not proceeded. Inside, on rutted dirt streets, I saw decrepit old people coming and going from apartments built into the decaying ruin.

A sign on the road through the village indicated that the last bus to Siena had departed hours ago. By now footsore and fatigued as well as hungry, I trudged toward a junction with the main highway. The prosperous American Elderhosteler had no choice but to hitchhike. I stuck out my thumb—probably not even the right gesture—and for fifteen minutes got nothing but puzzled stares from occasionally passing cars. Then in the distance I saw it—the Blue Bus. As it approached I could read "Siena Direct" in little yellow lights above the windshield. I don’t think I was at a real bus stop, but in my pocket I carried the return ticket I'd purchased for 90 cents that morning at the Tabak shop, so I stood in the road, and it stopped and opened its door. Back in the city and feeling triumphant, I stepped off at the Piazza Diavoli near our hotel. I was greeted by Tom, a member of our group, who was eager to fill me in on their day's excursion and to give me a slide show on the back of his little camera until the local bus he was waiting for pulled up and took him downtown.

I walked through the Hotel's entry arch and up the tree-lined promenade, a genial variation of the trail through the dark wood on Monte Maggiore. At the top, I enjoyed my last view of the towers of Siena in the waning light. Jan welcomed me with some bread and wine to break my fast. At our final meal together in the brightly lit dining room, I joined 35 Elderhostlers in toasting our caring hosts and bidding each other farewell.

During our visit to Fornello, Brenda reminded me twice that the final day of our trip was Yom Kippur, the highest holiday in the Jewish Calendar. I wished she hadn't mentioned it so I could have let it pass unnoticed.

I woke up Thursday morning feeling guilty—in part for the privilege of enjoying Italy during the time of year I would normally be staggering under my Fall quarter workload, and more specifically at the prospect of going on our scheduled gastronomic and wine tour of the Chianti region on this fast day. I hadnt attended a synagogue service in decades, but refraining from food for 24 hours and going into the woods alone on this holiday was one religious duty I had regularly observed. I decided to skip breakfast, excuse myself from the tour, and head for countryside. It took me a cranky uncaffeinated hour to negotiate buying a ticket from the Tabak shop and find the right bus stop, but by 11 a.m. I had reached Monteriggioni, where my Italian Alpine Club map indicated the beginning of an excursion leading to the top of Monte Maggiore.

I woke up Thursday morning feeling guilty—in part for the privilege of enjoying Italy during the time of year I would normally be staggering under my Fall quarter workload, and more specifically at the prospect of going on our scheduled gastronomic and wine tour of the Chianti region on this fast day. I hadnt attended a synagogue service in decades, but refraining from food for 24 hours and going into the woods alone on this holiday was one religious duty I had regularly observed. I decided to skip breakfast, excuse myself from the tour, and head for countryside. It took me a cranky uncaffeinated hour to negotiate buying a ticket from the Tabak shop and find the right bus stop, but by 11 a.m. I had reached Monteriggioni, where my Italian Alpine Club map indicated the beginning of an excursion leading to the top of Monte Maggiore.I got off the bus and bounded up the steep pedestrian approach to the castle famously described by Dante

As, when the fog is vanishing away,

As, when the fog is vanishing away,Little by little doth the sight refigure

Whate'er the mist that crowds the air conceals,

So, piercing through the dense and darksome air,

More and more near approaching tow'rd the verge,

My error fled, and fear came over me;

Because as on its circular parapets

Montereggione crowns itself with towers, 41

E'en thus the margin which surrounds the well

With one half of their bodies turreted

The horrible giants, whom Jove menaces

E'en now from out the heavens when he thunders. (Inferno Canto 31)

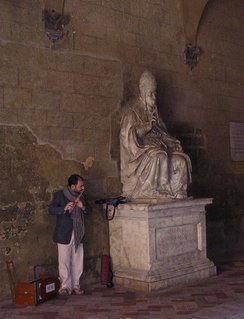

I wandered through the tiny village inside the fortress, sat for a moment in the empty chapel, and left 50 cents in the offering box. I paid a Euro to the lonely young man guarding the stairway that led to the top of the wall from which I could see the mountain towering in the mist.

In the car park on the south side of the wall, I found a large sign with a maps and historical information about the trail ahead. Like the piazza between the Siena Duomo and the Ospedale, this too was part of the Via Francigena, the pilgrim itinerary from Compostela to Rome that put me on a venerable path of discomfort, wanderlust and spiritual aspiration. My route through the wilderness of "Montagnola" would take me to the summit and then on what a sign called "La Grande Traversata," down to the villages of Fungaia and Santa Columba on the other side, where I could catch another bus back to the city.

In the car park on the south side of the wall, I found a large sign with a maps and historical information about the trail ahead. Like the piazza between the Siena Duomo and the Ospedale, this too was part of the Via Francigena, the pilgrim itinerary from Compostela to Rome that put me on a venerable path of discomfort, wanderlust and spiritual aspiration. My route through the wilderness of "Montagnola" would take me to the summit and then on what a sign called "La Grande Traversata," down to the villages of Fungaia and Santa Columba on the other side, where I could catch another bus back to the city.A dirt road led me into thick woods which occasionally opened up to fields, olive groves, and old villas and ended at an organic farm and meditation center named Ebbio, where several guests stood in the courtyard looking nervous and smoking cigarettes. Here the road gave way to a steep trail that tunnelled through forests of small trees, some thick with brush, others recently thinned and coppiced. I was serenaded by unfamiliar melodies that sounded as if they could only have been sung by birds called "larks."

Exertion and solitude and the growing distance from the valley occasionaly visible through a break in the trees contributed to the pleasant buzz in my head created by the emptiness in my stomach. A small trail branched to the left which I thought might lead to the summit. I noticed a cluster of delicate pink cyclamen growing in the deep shade at my feet, fresh blooms in mid-autumn.

Exertion and solitude and the growing distance from the valley occasionaly visible through a break in the trees contributed to the pleasant buzz in my head created by the emptiness in my stomach. A small trail branched to the left which I thought might lead to the summit. I noticed a cluster of delicate pink cyclamen growing in the deep shade at my feet, fresh blooms in mid-autumn.I followed the side trail uphill for several minutes, but rather than reaching a summit, it headed back downhill. Conscious that it was well past noon and that I hadnt seen any signs or trail markers for the last hour, I no longer could locate myself on the map with certainty. I returned to the patch of cyclamen and continued heading toward the westering sun, hoping soon to find a junction that would lead to the south and then east. The bird song had ceased and now in the distance I heard the whine of one, then two chainsaws. The trail came to a clearing at a junction of several tracks filled with deep mud, sign of the recent passage of skidders, the huge insect-like machines which drag timber out of the forest. Across a plateau miles ahead of me I could see

land that had recently been cleared but no evidence of civilization or indications of where I could make my way out of this endless Montagnola. I walked faster and then half ran toward the ugly sounds of the chainsaws but seemed to get no closer and found new paths heading off in all directions. I felt stirrings of fear and confusion. I checked my watch and told myself that if I found no landmark within ten minutes I would have to admit defeat, turn around and retrace my steps. Twenty minutes later, with an unmistakeable taste of panic in my mouth, I did just that.

land that had recently been cleared but no evidence of civilization or indications of where I could make my way out of this endless Montagnola. I walked faster and then half ran toward the ugly sounds of the chainsaws but seemed to get no closer and found new paths heading off in all directions. I felt stirrings of fear and confusion. I checked my watch and told myself that if I found no landmark within ten minutes I would have to admit defeat, turn around and retrace my steps. Twenty minutes later, with an unmistakeable taste of panic in my mouth, I did just that.The walk back was long and boring. Having neither reached the summit nor accomplished "La Grande Traversata," once I knew my way, I took an alternative dirt road down to the valley that passed by a memorial to WW II partisans who hid in this wilderness but finally were captured and executed by the Nazis. I passed several men with guns and dogs who were out hunting, probably for larks.

The road was steep, viewless and littered with trash. It emerged at Abbadia de Isola, which the historical signs told me was the site of an Abbey and military outpost for Siena that was rendered obsolete with the construction of Monteriggione back in the eleventh century. The buildings were standing, but restoration had not proceeded. Inside, on rutted dirt streets, I saw decrepit old people coming and going from apartments built into the decaying ruin.

The road was steep, viewless and littered with trash. It emerged at Abbadia de Isola, which the historical signs told me was the site of an Abbey and military outpost for Siena that was rendered obsolete with the construction of Monteriggione back in the eleventh century. The buildings were standing, but restoration had not proceeded. Inside, on rutted dirt streets, I saw decrepit old people coming and going from apartments built into the decaying ruin.A sign on the road through the village indicated that the last bus to Siena had departed hours ago. By now footsore and fatigued as well as hungry, I trudged toward a junction with the main highway. The prosperous American Elderhosteler had no choice but to hitchhike. I stuck out my thumb—probably not even the right gesture—and for fifteen minutes got nothing but puzzled stares from occasionally passing cars. Then in the distance I saw it—the Blue Bus. As it approached I could read "Siena Direct" in little yellow lights above the windshield. I don’t think I was at a real bus stop, but in my pocket I carried the return ticket I'd purchased for 90 cents that morning at the Tabak shop, so I stood in the road, and it stopped and opened its door. Back in the city and feeling triumphant, I stepped off at the Piazza Diavoli near our hotel. I was greeted by Tom, a member of our group, who was eager to fill me in on their day's excursion and to give me a slide show on the back of his little camera until the local bus he was waiting for pulled up and took him downtown.

I walked through the Hotel's entry arch and up the tree-lined promenade, a genial variation of the trail through the dark wood on Monte Maggiore. At the top, I enjoyed my last view of the towers of Siena in the waning light. Jan welcomed me with some bread and wine to break my fast. At our final meal together in the brightly lit dining room, I joined 35 Elderhostlers in toasting our caring hosts and bidding each other farewell.