The Church and the Synagogue

picture gallery

Sunday morning the glorious weather gave way to a familiar Italian drizzle. We packed and moved our bags to our new lodgings al Poste Vecchio and Jan picked our destination as San Giacomo dell Orio, a thirteenth century Church our map indicated contained a mixture of styles from thirteenth to seventeenth century. It was like a treasure hunt to find this new neighborhood, probably less than a quarter of a mile away, but a half hour of map reading and staring. The whole city is only 3 by 5 kilometres in extent but it contains 354 bridges, 177 small canals, 153 churches (each an architectural beauty), and 127 small squares.

Sunday morning the glorious weather gave way to a familiar Italian drizzle. We packed and moved our bags to our new lodgings al Poste Vecchio and Jan picked our destination as San Giacomo dell Orio, a thirteenth century Church our map indicated contained a mixture of styles from thirteenth to seventeenth century. It was like a treasure hunt to find this new neighborhood, probably less than a quarter of a mile away, but a half hour of map reading and staring. The whole city is only 3 by 5 kilometres in extent but it contains 354 bridges, 177 small canals, 153 churches (each an architectural beauty), and 127 small squares.

We arrived at San Giacomo just as mass was starting at 11:00 and had little choice but to sit down and join the local congregation of many ages, including young children, which filled all the seats. The service started with a folksong "Hallelujah" hymn accompanied by guitar, the same rendition they use in Jan's mom's Presbyterian church. After a few short readings from the Bible by members of the congregation, the priest took the pulpit. He was dressed in full regalia, green robe, white stole and more, and he looked the traditional part, with a bald crown and long, thick wavy white hair on the sides. His voice was fluent and cultivated but he read his sermon, and though I couldn't understand any of it, I got the impression it was provided by a higher authority. It was a good time to meditate and to admire the inside of the church, which included a 14th century wooden ceiling, a sixth century column, a stone lombard pulpit, and many paintings that we couldn't get close to. At the end of the sermon when the congregation rose, we made a discreet getaway out the door of the nave and admired the tower and some bits of celtic looking frieze embedded in the wall in another little square out back where restaurant waiters were setting up chairs and tables under tents.

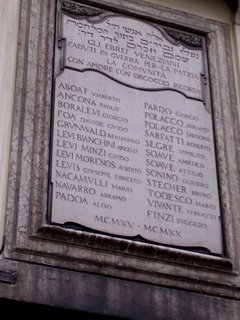

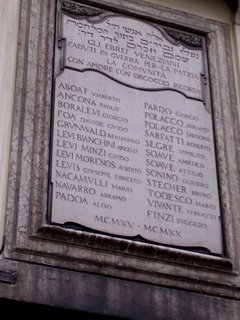

After another rest and picnic back in our room--we try to limit restaurant meals to one per day--we headed for the railroad station to reserve our seats to Siena. The same district of Canareggio contains the ghetto, home of Shylock and Jessica in The Merchant of Venice. To get there we needed to thread through crowds in a tourist district, but once we crossed the Cannareggio canal, the neighborhood was quiet. The buildings on either side of the narrow streets were taller than we'd seen elsewhere, one of them eight stories. On one wall was a stone plaque with names of people who had between 1915 and 1920 "fallen in the war, for the fatherland and the community recorded with love and pride." It included my mother's maiden name, Gruenwald. We crossed a bridge and came out on a large walled square with several shops selling Judaica.

To get there we needed to thread through crowds in a tourist district, but once we crossed the Cannareggio canal, the neighborhood was quiet. The buildings on either side of the narrow streets were taller than we'd seen elsewhere, one of them eight stories. On one wall was a stone plaque with names of people who had between 1915 and 1920 "fallen in the war, for the fatherland and the community recorded with love and pride." It included my mother's maiden name, Gruenwald. We crossed a bridge and came out on a large walled square with several shops selling Judaica. On one side was a holocaust memorial and a Jewish nursing home.

On one side was a holocaust memorial and a Jewish nursing home.

At the Ghetto museum we paid for a tour of the old synagogues. Our guide was a tall elegant woman with huge eyes and a mane of wild kinky hair. She wore a diamond studded star of David around her neck. She led us upstairs and unlocked a door to the German synagogue, a windowless room, tiny by comparison to any of the churches we've seen, with an elaborate gilt ark at one end and bima or pulpit at the other. She went through her spiel in highly accented but good English, with a strange mixture of boredom, suppressed anger and imploring eyes. She told the history of the ghetto. Jews had lived all over the city in its early days, performing essential functions of money lending, today known as finance, that were forbidden to Christians. In the late fourteenth century, an edict was issued requiring the Jews to live in this small section of the city, which was gated and locked at night. Whenever they left this section they had to wear yellow armbands. Rather than one community, there were four, distinguished by their countries of origin--two northern European Ashkenazi and two Spanish and African Sephardic--each with its own synagogue. The synagogues themselves all have upper gallieries, where women could watch but not participate in the services, separated from the men below by latticework screens. The communities thrived and the population increased to over 8000 people packed into a tiny space, requiring the construction of more and more stories on the buildings.

In the next synagogue, the Polish Ashkenazi, she continued the narrative. The ghetto was opened by Napoleon and the Jews were allowed to move out, but then closed again after his defeat, and then opened again with the establishment of the Republic in the later 19th century. The fascists under Mussolini required all Jews to register and move back to the ghetto. As the war proceeded, they turned the lists over to the Nazis, who came in and deported all the inhabitants to concentration camps. Only a few families returned, but now about 400 Jews are left in Venice.

The third Synagogue, a Sephardic one, was elaborate Baroque, designed by Longhi, the architect of Salute Cathedral. Jews were forbidden from practising trades or owning land, so the construction of the synagogues was performed by hired craftsmen. Our guide attends this synagogue but doesn't live in the ghetto. She told us she would prefer to since it is now one of the more desireable neighborhoods in Venice because of its lack of crowds and proximity to the railroad station and parking garage. In response to our questions, she went on to describe the difficulty of being a resident of this dream city. The desire for preservation means that you cannot do any renovations or repairs on the ancient buildings without official permission. When a pipe broke under her living room floor, she wasn't allowed to tear up the antique terrazo, but had to put in a whole new plumbing system. People have to carry their groceries through the narrow streets and over bridges. There is nowhere for children to play. And the taxes, rents and property values keep going up as rich Americans and Japanese buy residences in the city which they usually leave uninhabited. So the indigenous population of Venice has decreased by 25% in the last five years.

A Shakespearean experience of Venice--what appears as good is not so good. Jews are victims of Christians, loyal to one another but also their own worst enemies. The city of love and glamor has an underside of greed and disfunction.

The rain got heavier. The canal smelled stronger. We came back to our hotel and dressed for dinner at the classy restaurant affiliated with our hotel, the Poste Vecchi. We took the tourist menu. The pasta with funghi (mushrooms), the sea bass and the crème caramel were all extraordinary. Next to us sat two parents and a college age daughter from Australia. He was a lawyer and she was a professor. Our conversation lasted late.

The rain got heavier. The canal smelled stronger. We came back to our hotel and dressed for dinner at the classy restaurant affiliated with our hotel, the Poste Vecchi. We took the tourist menu. The pasta with funghi (mushrooms), the sea bass and the crème caramel were all extraordinary. Next to us sat two parents and a college age daughter from Australia. He was a lawyer and she was a professor. Our conversation lasted late.

At 2:00 A.M. I woke up and couldn't get back to sleep. I worked on the journal until 5:30 A.M.

Sunday morning the glorious weather gave way to a familiar Italian drizzle. We packed and moved our bags to our new lodgings al Poste Vecchio and Jan picked our destination as San Giacomo dell Orio, a thirteenth century Church our map indicated contained a mixture of styles from thirteenth to seventeenth century. It was like a treasure hunt to find this new neighborhood, probably less than a quarter of a mile away, but a half hour of map reading and staring. The whole city is only 3 by 5 kilometres in extent but it contains 354 bridges, 177 small canals, 153 churches (each an architectural beauty), and 127 small squares.

Sunday morning the glorious weather gave way to a familiar Italian drizzle. We packed and moved our bags to our new lodgings al Poste Vecchio and Jan picked our destination as San Giacomo dell Orio, a thirteenth century Church our map indicated contained a mixture of styles from thirteenth to seventeenth century. It was like a treasure hunt to find this new neighborhood, probably less than a quarter of a mile away, but a half hour of map reading and staring. The whole city is only 3 by 5 kilometres in extent but it contains 354 bridges, 177 small canals, 153 churches (each an architectural beauty), and 127 small squares.We arrived at San Giacomo just as mass was starting at 11:00 and had little choice but to sit down and join the local congregation of many ages, including young children, which filled all the seats. The service started with a folksong "Hallelujah" hymn accompanied by guitar, the same rendition they use in Jan's mom's Presbyterian church. After a few short readings from the Bible by members of the congregation, the priest took the pulpit. He was dressed in full regalia, green robe, white stole and more, and he looked the traditional part, with a bald crown and long, thick wavy white hair on the sides. His voice was fluent and cultivated but he read his sermon, and though I couldn't understand any of it, I got the impression it was provided by a higher authority. It was a good time to meditate and to admire the inside of the church, which included a 14th century wooden ceiling, a sixth century column, a stone lombard pulpit, and many paintings that we couldn't get close to. At the end of the sermon when the congregation rose, we made a discreet getaway out the door of the nave and admired the tower and some bits of celtic looking frieze embedded in the wall in another little square out back where restaurant waiters were setting up chairs and tables under tents.

After another rest and picnic back in our room--we try to limit restaurant meals to one per day--we headed for the railroad station to reserve our seats to Siena. The same district of Canareggio contains the ghetto, home of Shylock and Jessica in The Merchant of Venice.

To get there we needed to thread through crowds in a tourist district, but once we crossed the Cannareggio canal, the neighborhood was quiet. The buildings on either side of the narrow streets were taller than we'd seen elsewhere, one of them eight stories. On one wall was a stone plaque with names of people who had between 1915 and 1920 "fallen in the war, for the fatherland and the community recorded with love and pride." It included my mother's maiden name, Gruenwald. We crossed a bridge and came out on a large walled square with several shops selling Judaica.

To get there we needed to thread through crowds in a tourist district, but once we crossed the Cannareggio canal, the neighborhood was quiet. The buildings on either side of the narrow streets were taller than we'd seen elsewhere, one of them eight stories. On one wall was a stone plaque with names of people who had between 1915 and 1920 "fallen in the war, for the fatherland and the community recorded with love and pride." It included my mother's maiden name, Gruenwald. We crossed a bridge and came out on a large walled square with several shops selling Judaica. On one side was a holocaust memorial and a Jewish nursing home.

On one side was a holocaust memorial and a Jewish nursing home.At the Ghetto museum we paid for a tour of the old synagogues. Our guide was a tall elegant woman with huge eyes and a mane of wild kinky hair. She wore a diamond studded star of David around her neck. She led us upstairs and unlocked a door to the German synagogue, a windowless room, tiny by comparison to any of the churches we've seen, with an elaborate gilt ark at one end and bima or pulpit at the other. She went through her spiel in highly accented but good English, with a strange mixture of boredom, suppressed anger and imploring eyes. She told the history of the ghetto. Jews had lived all over the city in its early days, performing essential functions of money lending, today known as finance, that were forbidden to Christians. In the late fourteenth century, an edict was issued requiring the Jews to live in this small section of the city, which was gated and locked at night. Whenever they left this section they had to wear yellow armbands. Rather than one community, there were four, distinguished by their countries of origin--two northern European Ashkenazi and two Spanish and African Sephardic--each with its own synagogue. The synagogues themselves all have upper gallieries, where women could watch but not participate in the services, separated from the men below by latticework screens. The communities thrived and the population increased to over 8000 people packed into a tiny space, requiring the construction of more and more stories on the buildings.

In the next synagogue, the Polish Ashkenazi, she continued the narrative. The ghetto was opened by Napoleon and the Jews were allowed to move out, but then closed again after his defeat, and then opened again with the establishment of the Republic in the later 19th century. The fascists under Mussolini required all Jews to register and move back to the ghetto. As the war proceeded, they turned the lists over to the Nazis, who came in and deported all the inhabitants to concentration camps. Only a few families returned, but now about 400 Jews are left in Venice.

The third Synagogue, a Sephardic one, was elaborate Baroque, designed by Longhi, the architect of Salute Cathedral. Jews were forbidden from practising trades or owning land, so the construction of the synagogues was performed by hired craftsmen. Our guide attends this synagogue but doesn't live in the ghetto. She told us she would prefer to since it is now one of the more desireable neighborhoods in Venice because of its lack of crowds and proximity to the railroad station and parking garage. In response to our questions, she went on to describe the difficulty of being a resident of this dream city. The desire for preservation means that you cannot do any renovations or repairs on the ancient buildings without official permission. When a pipe broke under her living room floor, she wasn't allowed to tear up the antique terrazo, but had to put in a whole new plumbing system. People have to carry their groceries through the narrow streets and over bridges. There is nowhere for children to play. And the taxes, rents and property values keep going up as rich Americans and Japanese buy residences in the city which they usually leave uninhabited. So the indigenous population of Venice has decreased by 25% in the last five years.

A Shakespearean experience of Venice--what appears as good is not so good. Jews are victims of Christians, loyal to one another but also their own worst enemies. The city of love and glamor has an underside of greed and disfunction.

The rain got heavier. The canal smelled stronger. We came back to our hotel and dressed for dinner at the classy restaurant affiliated with our hotel, the Poste Vecchi. We took the tourist menu. The pasta with funghi (mushrooms), the sea bass and the crème caramel were all extraordinary. Next to us sat two parents and a college age daughter from Australia. He was a lawyer and she was a professor. Our conversation lasted late.

The rain got heavier. The canal smelled stronger. We came back to our hotel and dressed for dinner at the classy restaurant affiliated with our hotel, the Poste Vecchi. We took the tourist menu. The pasta with funghi (mushrooms), the sea bass and the crème caramel were all extraordinary. Next to us sat two parents and a college age daughter from Australia. He was a lawyer and she was a professor. Our conversation lasted late.At 2:00 A.M. I woke up and couldn't get back to sleep. I worked on the journal until 5:30 A.M.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home